Apple and Google have been summoned to a Senate hearing on privacy matters, partly in the light of revelations that both firms track historic user locations in their devices. Apple's facing an early, highly speculative federal lawsuit on the matter. And it all focuses on alleged violations of user privacy. But in the very near future, you'll probably actively prefer that Apple and Google track your location--albeit under tightly defined privacy protection rules.

Apple's current PR kerfuffle rests on a file called "consolidated.db" hidden deep within the code of iOS and which never gets sent anywhere. The file contains a time-coded list of the phone's approximate position based on previously geo-located cell phone masts and known Wi-Fi networks. It only became an issue when researchers revealed last month how it could be used to track a user's position, historically speaking, and the press went crazy about it. Steve Jobs has now, allegedly, weighed in on the matter saying Apple doesn't track user location, and he's right--because Apple doesn't get to see it and the file is for internal use in the iOS device. It's possibly even a bug left over from an earlier experiment at fast-acquisition of a previously known network or for swifter A-GPS location locks.

Google has a similar file buried in Android, and according to Steve Jobs and other commentators it most definitely does use it to work out where you've been, for its own mysterious purposes.

In fact, if you look at some recent and older patents from Apple, bearing in mind the current vogue for social sharing and the upcoming wave of NFC wireless credit card tech, you're going to prefer Apple and Google track your whereabouts all the time.

Apple filed a patent numbered 12/553,554 last month with the USPTO and sites like Gawker haveused it to argue Apple has plans to "spy" on its users, and even to hint the consolidated.db file is no accident--it's the first stage in Apple's plans. But glancing at the patent it's immediately obvious that the future "location history database" file it mentions has very useful, innocuous purposes. Apple suggests the file could be used to geo-tag photographs taken by the iPhone's camera, presumably long after you snapped the image and forgot where it was. This could help you use the images in systems like its own iPhotos app--which has a "places" feature--as well as other online photo databases.

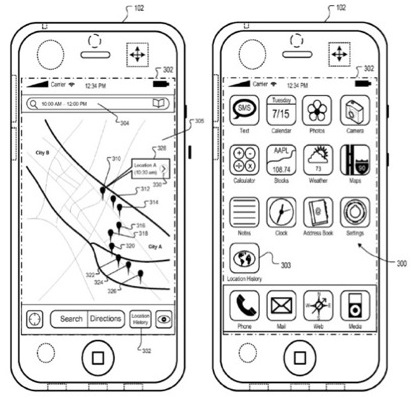

Apple filed a patent numbered 12/553,554 last month with the USPTO and sites like Gawker haveused it to argue Apple has plans to "spy" on its users, and even to hint the consolidated.db file is no accident--it's the first stage in Apple's plans. But glancing at the patent it's immediately obvious that the future "location history database" file it mentions has very useful, innocuous purposes. Apple suggests the file could be used to geo-tag photographs taken by the iPhone's camera, presumably long after you snapped the image and forgot where it was. This could help you use the images in systems like its own iPhotos app--which has a "places" feature--as well as other online photo databases.Apple even mentions the history file could be useful for users to "augment a travel time-line with content," in some kind of post-vacation multimedia creation, or to form part of a "personal 'journal' which can be queried at a later time" (a Captain's Log app, anyone?). It's all about mapping and added value, suggests the text--and though it does talk about how third party apps could call the data through an API, these too are "location aware" apps like the one's we're all signing up to in droves. The specifics of the patent also highlight the location history is approximately defined based on triangulation from known positional data like cell masts and Wi-Fi grids, because using a GPS system for permanent geo-coding would consume too much battery life.

If we dig back in Apple's patent history, we find the firm has long pursued very complex plans for geo-located apps and facilities in iOS. Back in 2009, Apple filed a number of location-based patents relating to turn-by-turn navigation--some of which, by definition, rely on a location history file to work. These are tricks like "intelligent route guidance" and "adaptive route guidance based on preferences" which suggest different routes to a GPS nav destination based on how you navigate there habitually, and perhaps with knowledge about current road conditions thrown in. There's also a "route sharing and location" aspect to the patents, which lets you send historic navigation information to a friend via some social sharing tool so they can copy, for example, that handy route to work you know that avoids a traffic blackspot. One implementation of this tech is a live position-share that happens over the network, which could help you meet up with a pal in a new location. All of these seem useful, and all of them require some degree of location history file--Apple even mentions a facility for users to turn on a special accurate "recording" of location, to help with navigation or possibly sports.

Another patent imagines an iPhone docked to a smart car interface, sharing navigation information and even specific apps for your car--again a system that could be very useful, and which would also require a location history file (or two, or three).

Yet another Apple patent, this time from 2010 and ostensibly concerning an updated alerts system and dynamic app icon alerts and loading, actually is all about location-aware advertising and even automated location-sensitive app uploads. It envisages the kind of location-sensitive ads that would pop up as you strolled near a coffee shop or walked near a tourist location in a new city, ads that would detect where you are and perhaps even tempt you in with a coupon (Groupon-, or perhaps Facebook-style). These are the kind of dynamic location-based ads that would be useful and could work to boost business at ad partners ... and it's easy to imagine them having a historic component: "We've noticed you walked by our coffee shop a couple of times this week. If you were a member of our loyalty scheme, you'd've saved $2.50 by now!".

This sort of functionality may deliver a type of advertising many consumers could prefer--as it's sharply tailored to their needs, rather than irrelevant ads--and it too requires some sort of location history. And don't tell us Google, king of social graphing and placing consumer-tailored ads on everything, everywhere, doesn't plan exactly this sort of uses for its location data from Android smartphones or tablets.

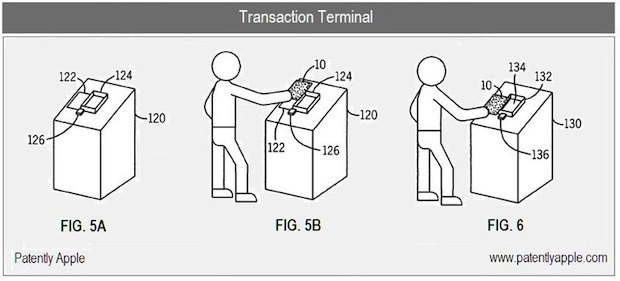

With the imminent arrival of the NFC smartphone "wave and pay," location data and historic location data becomes even more important. Apple's also extensively patented this technology, and has imagined that location data could be used as part of a security check--detecting that, for example, your phone is actually at the NFC-enabled ATM it's data feed is suggesting it is, and that no one has spoofed your data. It's also possible that you'd want Apple to track your phone's location to work out if, while you've been hovering in the New York area all day, at 2 a.m. someone with faked NFC credit credentials that match yours tries to buy casino chips in Las Vegas. This sort of security protocol will become increasingly important as we trust our smartphones to be our wallets as well as our mobile communicators full of personal data and photographs, and it too relies on some form of location history being stored in your device or at Apple or Google's data centers.

And, incidentally, if you're the kinda down on Microsoft for not pulling the same kind of location-recording tricks as Apple and Google (perhaps a hint at exactly how far behind the smartphone curve MS has slipped) then it also looks like Windows Phone 7 frequently sends neat little data packets to MS HQ, each of which contains data on Wi-Fi networks encountered and GPS info...plus a unique phone ID.

Less annoying adverts, super-smart navigation, location-based and journey-habit-based special offers, enhanced wireless credit card security ... why wouldn't you let your phone (and, possibly, Apple and Google) record your approximate location? There'll be questions of trust, and hack-proof security, but pretty soon you're not even going to think twice about it.

No comments:

Post a Comment